Another selfish tool–Endpoint for VS Code

I recently was actually building a personal app that integrated with 5 different third-party APIs, each having different authentication requirements or API keys to navigate the calls. I normally would just use .http files and be done with it, but I’m a GUI person at heart and as much as I was iterating with the app and these services (across sandbox/prod environments too), navigating the single .http file just as raw text was getting frustrating for me honestly. I was already using the Rest Client for VS Code extension which is great and the absolute simplest and likely widely used. I tried a few other extensions in the marketplace but they have really shifted to be ‘enterprise’ and SaaS based and I just didn’t need all those capabilities or want a service.

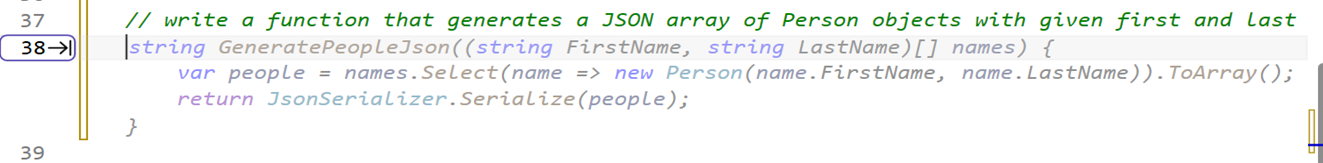

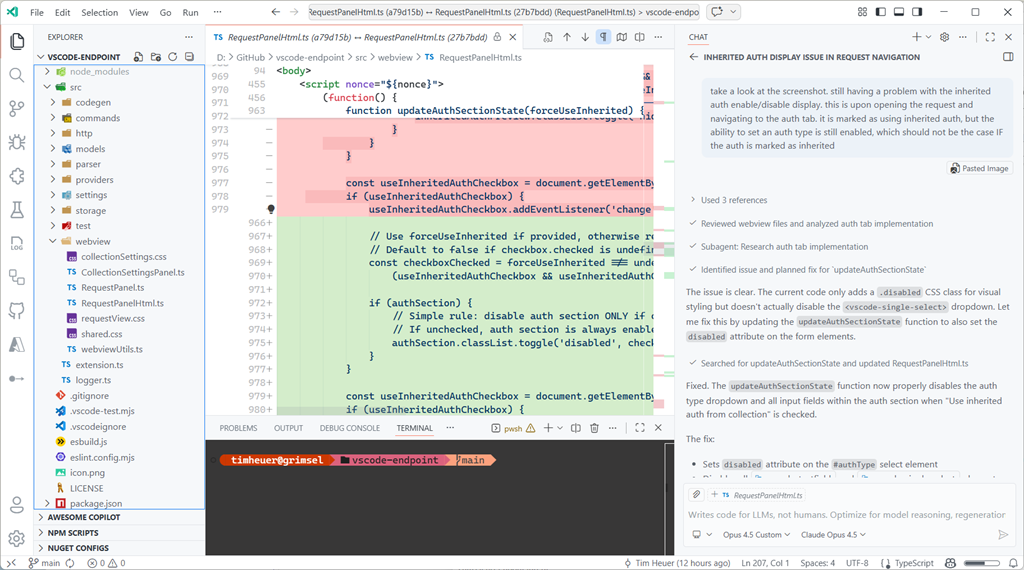

So I just decided to have Copilot help me and iterate on a plan and implementation…and decided to call it “Endpoint” and here we are.

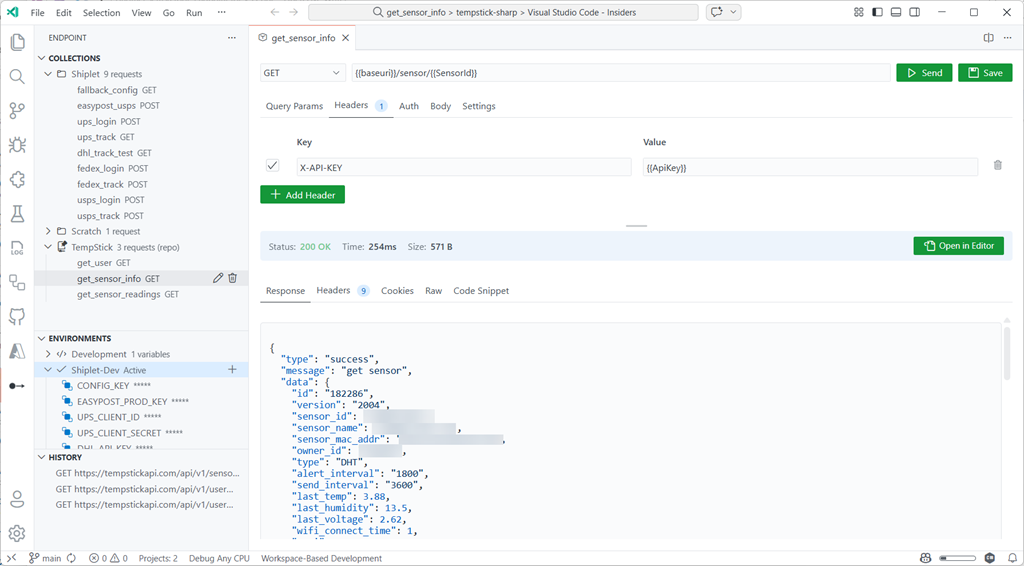

It’s basically a REST client, but biased hard toward *staying inside the editor* and keeping your requests portable.

What problem this is trying to solve (for me)

There are already a lot of ways to “test an endpoint.” This isn’t meant to be a hot take about existing tools. This is more like: what do I personally want when I’m iterating fast and gives me a structured way of seeing output?

For me the pain points are:

- I want an API client that feels like part of VS Code: Same theme, same UX expectations, no “external app” vibe.

- I want requests to be roaming with me, or shareable in the repo just like .http files: If a request is useful, I want it in source control not in a service.

- I want multi-step flows to be easy: The classic “call login, grab token, call the real endpoint” loop.

- I wanted some level of compatibility with the .http format because I do use multiple tools

Endpoint is my attempt at optimizing those loops for me.

But don’t `.http` files already do this?

Yep — and that’s actually part of the point. I like `.http` files because they’re **portable**, **diffable**, and **live well in source control**. If all you need is “a request in a file that I can run,” `.http` is a great answer and REST Client is a great simple tool!

Endpoint leans into that by supporting import/export so you can move between the file format and the GUI workflow. In other words: even if you don’t start in `.http`, you can end up there (and vice versa). Endpoint isn’t trying to replace that model; it’s a selfish tool for GUI lovers who want something around the same workflow and make it easier, intuitive, and graphical:

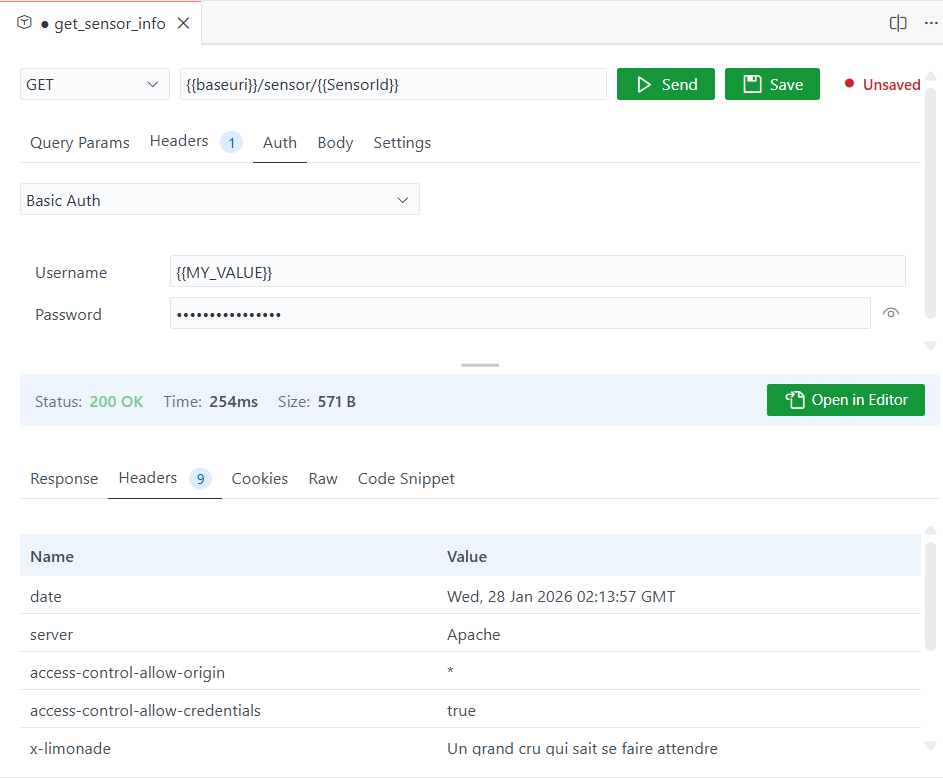

- A native GUI for editing params/headers/auth/body without living in raw text all day

- Collections + defaults (shared headers/auth/variables) so you don’t repeat yourself

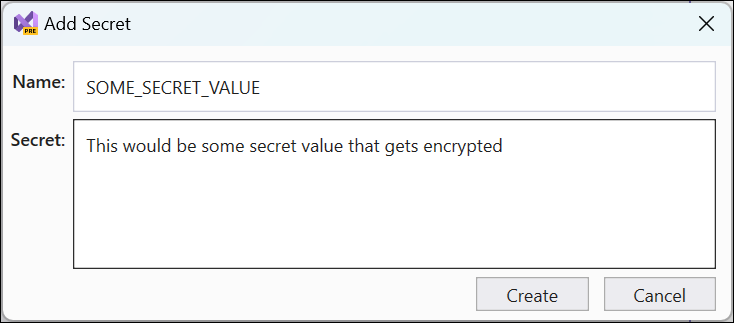

- Environments that are quick to switch (and don’t accidentally leak secrets into git)

- Chaining + pre-requests for the auth/multi-step reality of modern APIs

- Code snippets if you need bridge from “it works” to “ship it in the app”

So if you already have `.http` files you love, cool — keep them. Endpoint is me acknowledging that the file format is great, but I personally wanted fewer papercuts while iterating.

Why not just persist everything as `.http` all the time? Mostly because the GUI needs a structured model (headers on/off, auth type fields, body mode, collection defaults/inheritance, secret handling, etc.). You *can* represent a lot of that in text, but you quickly end up either losing fidelity or inventing extra conventions. I chose to persist a richer model for the day-to-day workflow, and then use import/export as the compatibility layer when you want the portable file representation.

What about other existing GUI tools?

Yep, there are a good set of ones out there that are incredibly rich. Some are mostly freemium models too though. And some may not be able to be used in certain environments because of organizational policies. These are all fantastic tools, but they didn’t work for my every need, so I just selfishly wanted my own flow…which I acknowledge may not work for anyone else’s need :-). But by all means, the ones out there are super popular, incredibly powerful, and do way more for advanced scenarios.

What Endpoint gives me (in practice)

At a high level, it’s a request builder + response viewer that stays inside VS Code. The part I care about isn’t the checklist of features — it’s that the whole loop (edit → send → inspect → tweak → repeat) happens without me leaving the editor.

The mental model is simple: Collections for grouped project scopes and saved requests, Environments for variables, and a simple split request/response view with the most important things at the surface.

The small set of things I reach for most:

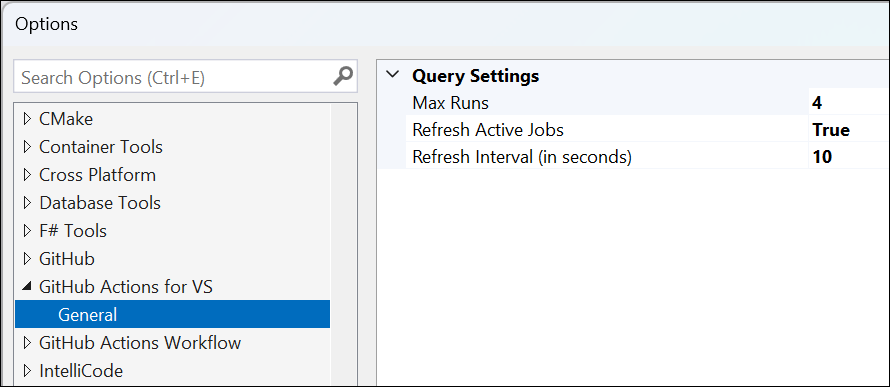

- Variables + `.env` support so I’m not hardcoding base URLs or keys (supports .env files, or stored in VS Code SecretStorage)

- Repeatable/shared/inherited properties for headers and auth

- Chaining / pre-requests for “login then use token” flows

- Roaming saved collections across machines – even when I’m not wanting to persist these to team repo yet

- Export/import for when I want to serialize for sharing broadly if needed

I’m still iterating, but those cover 90% of my day-to-day.

Summary

This isn’t meant to replace every API tool ever as I mentioned. Nearly every tool I create starts for extremely selfish reasons. It’s optimized for the thing I do the most: tight inner-loop iteration while already living in VS Code.

If you need heavyweight collaboration features, deep test scripting, or a bunch of external integrations, this isn’t going to be it and you might still prefer something else.

But if your primary pain is “I just want to hit this endpoint while I’m validating, and I don’t want to leave the editor and have the same editor UI,” then this has been a meaningful productivity boost for me and maybe for you.

Feel free to try it out and log issues as you face them using “Report Issue” in VS Code!